Researchers look to nature to pull water from the air›››

FLOOD INSURANCE

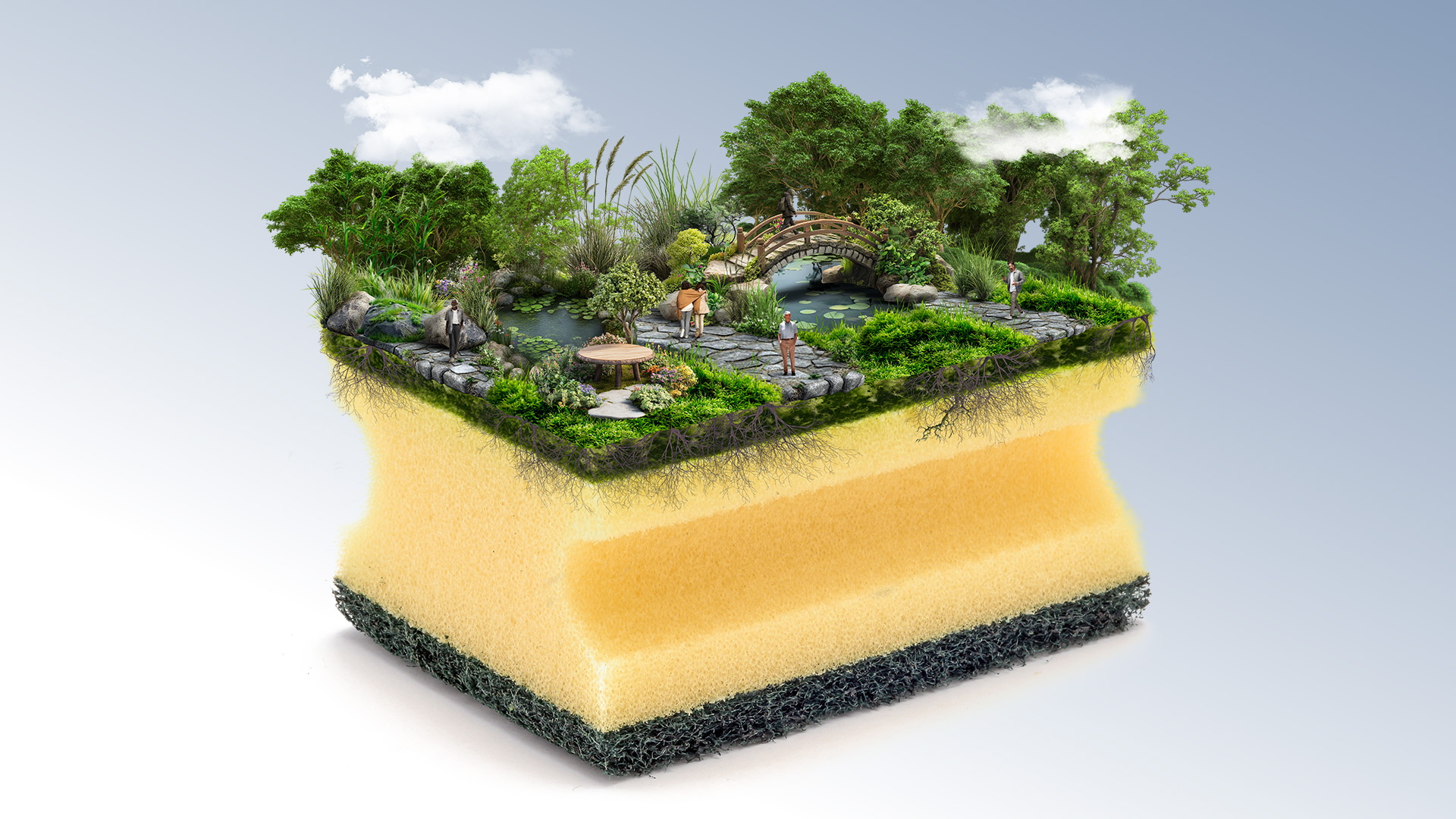

‘Sponge cities’ harness nature to manage – and betteruse – rain from storms supercharged by climate change 23 Sep 2025

Storms are becoming stronger, wetter and deadlier. You can thank a warmer, moister atmosphere and heating oceans as the extreme storms they feed produce more rain, stronger winds and heavier flooding. In 2024 alone, hurricanes Helene and Milton left hundreds of billions of dollars in damages while flooding in Afghanistan and Pakistan was blamed for more than a thousand deaths.

Watch video on sponge cities here.

Cities, in particular, may be feeling the effects of these killer storms more intensely than the countryside.

For one thing, urban areas draw more rain: Skyscrapers often slow storms, letting them drop more precipitation in a relatively small area. Pollution like auto exhaust also seeds clouds. And heat rising from pavement and concrete creates convectional rainfall.

IMAGE: ABJAD DESIGN

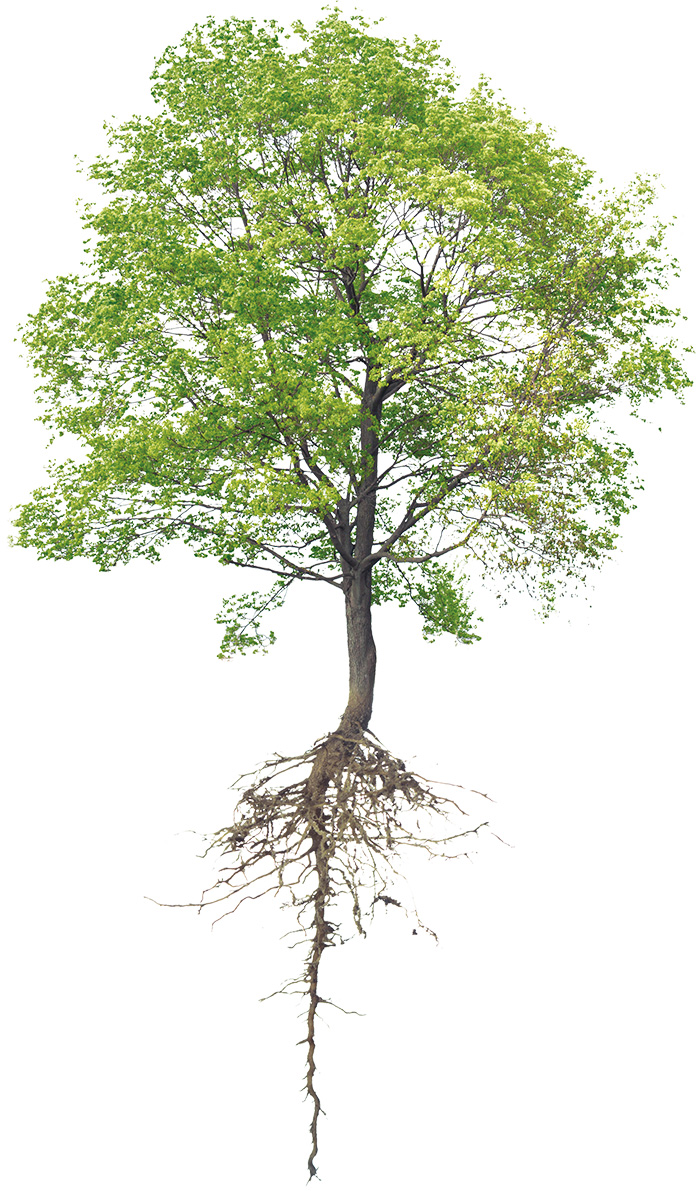

IMAGE: ABJAD DESIGNSponge cities don’t just protect residents from flooding. They also provide relief from extreme heat, says the University of Adelaide’s Scott Hawken. “In cities like Adelaide, heat waves are even more deadly than flooding. They kill a lot of people: the vulnerable, the young and the old. We need to think about how to keep our cities cooler during these extreme events and design parks and gardens to generate cool airflows and bring the surface temperature down,” he says. Read more›››

The best way to do that is to use well-watered and irrigated vegetation to set up cool airflows throughout the city, Hawken says. “It’s not just having a park here. It’s strategic, like a natural air conditioner. We need to think of these larger park systems woven in amongst our cities. These parks need to be well-watered, but that shouldn’t be a problem if resources are used wisely, he says. “Most of the time there is plenty of water in our cities, but we just don’t use it carefully,” he says.

“Many cities around the world are running out of water, but those cities often don’t take care of their water. It’s only when the drought kicks in that the penny drops. But by then it’s too late. We don’t have the systems in place.” Urban oases in Abu Dhabi helped cool surrounding temperatures by up to 2.2 degrees Celsius, according to a study by Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence and the tech giant IBM.

Artificial intelligence-enabled technology helped analyze decades of satellite data and provided insights on how vegetation and water bodies make a significant impact on heat islands in the city. Masdar Park in the Masdar City neighborhood had a 2.2-degree cooling effect in that area, the researchers found. Umm Al Emarat Park, one of the largest and oldest parks in the city, brought down the surrounding temperature by 1 degree.

The researchers suggest the technology can enable sustainable design and help urban planners identify other areas that could benefit from green spaces. ‹‹‹ Read less

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences says the effect has become more pronounced over the past two decades.

Listen to the story here

“This is everywhere,” Dev Niyogi, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and paper co-author, tells the Washington Post. “The magnitude of the impact will vary. But just the way we treat urban heat islands, we should start treating urban rainfall effect as a feature associated with urbanization.”

And some cities that have not previously been associated with flooding are finding that the changing climate may require a different kind of urban planning.

Exhibit A: Abu Dhabi, where record-breaking April 2024 storms brought a year’s worth of rain to the Gulf city in just a day.

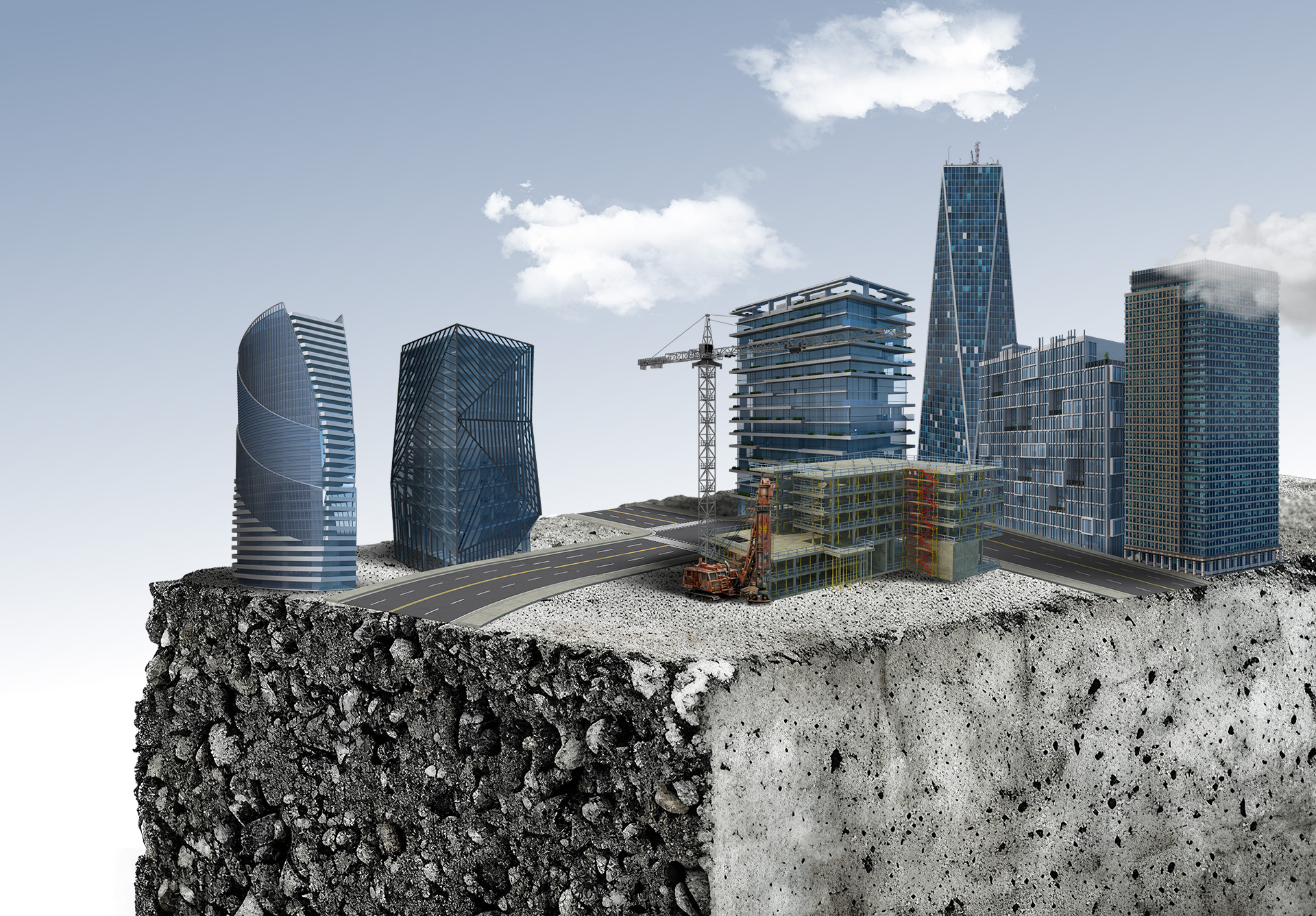

FROM THE GROUND UP

Chinese landscape architect Kongjian Yu has been thinking about that different kind of urban planning for decades.

He won the Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize (“Oberlander Prize”) in 2023 for his concept of “sponge cities,” which has inspired projects not only in China, but France, Russia, Indonesia, Thailand and the United States. Yu’s company Turenscape has contributed to more than 600 projects in 200 cities.

The concept relies on nature – through trees, parks and ponds – and good design to protect cities from flood waters. In essence, rather than rely on concrete drainage systems and flood walls, it makes the city itself a “sponge” to better absorb rainfall.

“There’s a misconception that if we can build a flood wall higher and higher, or if we build the dams higher and stronger, (then) we can protect a city from flooding,” Yu tells CNN. “(We think) we can control the water … that is a mistake.”

Watch: Climate Change, the Classroom Crisis

The stakes are high. An Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report says 700 million people live in areas where rainfall extremes have risen. This number is expected to grow as global temperatures increase.

CELEBRATING THE WATER

Scott Hawken, director of the Landscape Architecture and Urban Design program at the University of Adelaide’s School of Architecture and Civil Engineering, uses sponge city principles in his work. It’s about celebrating the water on site, he says.

“This development of the sponge city is about the necessity to manage water in a more intelligent way. It allows water to infiltrate into the landscape and slow it down, to manage it on site rather than what has been done throughout most of the 20th century, which is to expel the water from the city rapidly,” he tells KUST Review.

As Hawken tells it, preparing urban areas to better withstand flooding isn’t just an issue with physical infrastructure, like swapping out concrete gutters for absorbent plants and sandier soils. It requires a change in social perspectives as well.

“The 20th century perspective (sees) water or flooding being a problem or a nuisance.

That’s one cultural perspective that inspired overengineered approaches which haven’t really valued water in the way that it should be valued.

Instead, Hawken suggests looking to communities that consider flooding a part of life, like the cities and settlements of Southeast Asia that have weathered monsoon climates for hundreds of years and longer.

“Floods there are not viewed as a risk. But in the Western context we really fear floods. They’re out of mind until they’re around us, and then we panic rather than thinking into the future and planning to live with floods and work with them on site.”

And where you can’t work with them?

“We’ve also built in a lot of areas which we shouldn’t, like on flood plains.”

MANAGING THE WATER

Hawken isn’t just concerned with creating a landscape that better absorbs water but cities that manage the rain wisely.

“The irony is often you have a very wet landscape that has a lot of water but also has to pipe water in because it’s not using water in a smart enough way. It isn’t recycled, filtered and reused.

“People have a resistance to that. But some of the traditional societies have been reusing and recycling water in intelligent ways for a long time. We need to get over that. The technology is certainly there.

“The filtered and recycled water is often much cleaner than the water that’s not,” Hawken says.

Singapore, he says, is an example of a city that is successfully reusing and recycling its water resources.

“A lot of the technology that was developed in Australia has been exported to places like Singapore. Now they’ve taken those ideas and run with them, probably doing a better job than anywhere else.”

DESERT SOLUTIONS

Dubai entrepreneur Chandra Dake has also been thinking about managing flood waters and collecting rain for reuse. His inspiration: the United Arab Emirates’ desert sands.

Dake and his company, Dake Rechsand, use the plentiful sand to create permeable materials that not only allow water to pass through but filter it on its way to underground honeycomb storage tanks. These tanks keep the water fresh without chemicals or electricity.

“Every nook and corner, every junction, can become a storage house of water,” he says. “That reduces the burden of centralized storm management, which is normally implemented in advanced cities across the globe.”

He points to a project in Beijing that used his technology to address chronic flooding problems that led to frequent traffic jams.

“This area that used to flood is now able to harvest every drop of water. The surface is now used for a recreational facility. All the rainwater goes underneath it. After implementing it for the last two, three years there’s no more flooding, not even one traffic jam. And the water? It’s literally like distilled water.”

Saving the water from just one storm would be a huge benefit for UAE cities that rely mostly on energy-hungry desalination technology, he says.

That record-breaking 2024 storm? The water could have been used for two or three months cleaning roads, improving irrigation and watering greenery, he says.

Instead, it went to waste. “All of that water was discarded. Not even one cubic meter was used.” Dake says his technology can easily be integrated into an existing infrastructure. “You can build a road. You can build paving. You can build anything. And these can be retrofitted as well.”

The materials are suitable for both hot and cold climates, Dake tells KUST Review. “And one important element is these materials are made from desert sand. Desert becomes a solution for global problems.

“We will see enormous social, environmental and economical benefits,” he predicts.

More like this: A river runs over it

Get the latest articles, news and other updates from Khalifa University Science and Tech Review magazine